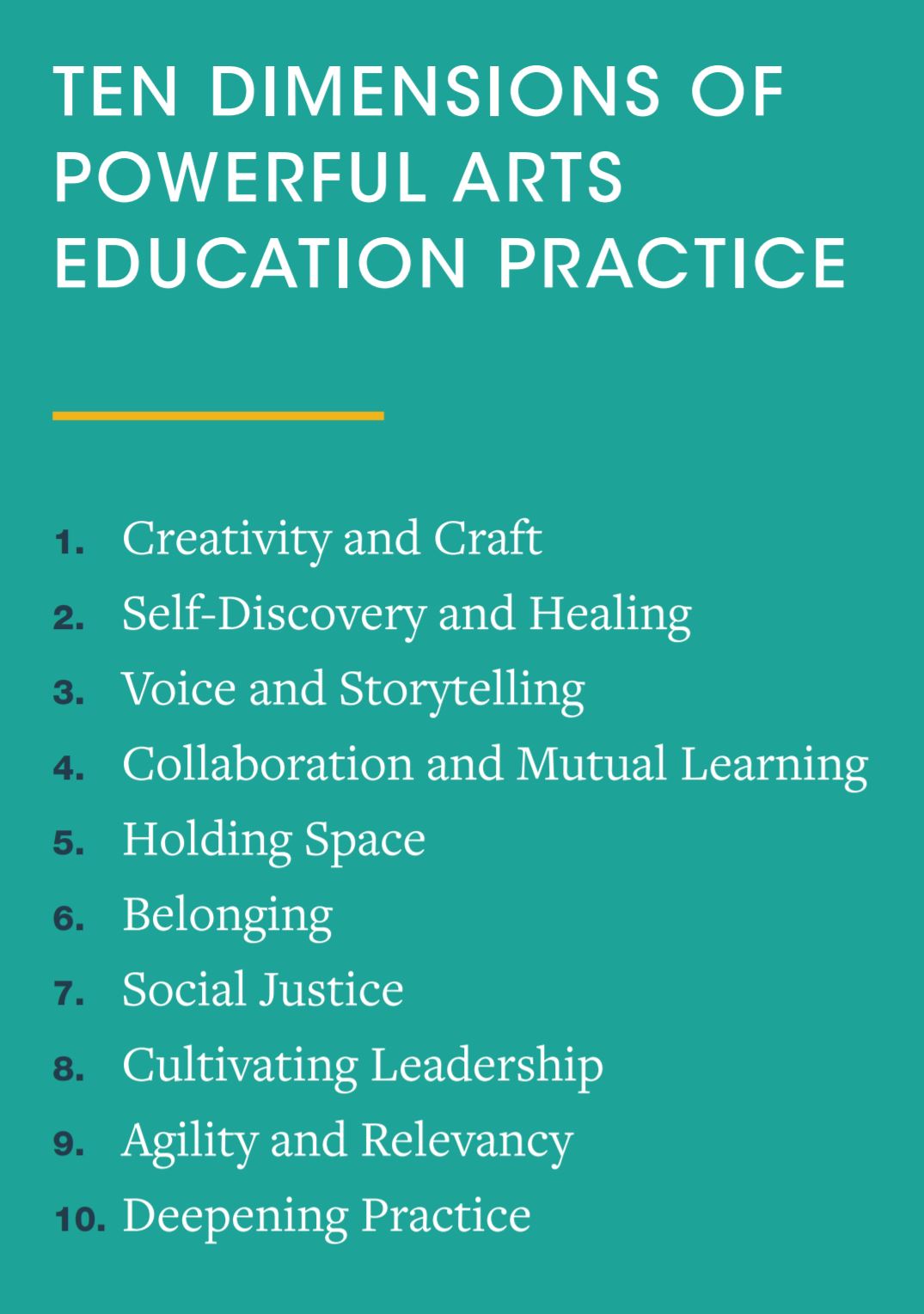

Ten dimensions of powerful arts education

Part of the answer to these questions lie within our new report, Ten Dimensions of Powerful Arts Education Practice. The ten dimensions are, in essence, a framework that describes the approaches and conditions that suggest powerful arts education is taking place. It was created by and with the input of accomplished arts education practitioners and youth, through a process led by arts researcher Lauren Stevenson and master arts education practitioner Sarah Crowell. Perhaps most important is that the framework is flexible enough to be applied in a variety of learning environments, with many different types of individuals and groups.

Stevenson and Crowell took great care to describe each of the dimensions that emerged from their work with the practitioners and youth, such as attending to creativity and craft and cultivating leadership among both teaching artists and youth. Each dimension is illuminated by specific examples of how the practices might look and feel in the learning environment. A resource guide at the end of the document provides links to further reading on each of the dimensions described.

The framework represents the best thinking of some of the Bay Area’s leading practitioners in arts education. It incorporates youth voice in its design and development. Just as significant is that the framework is not a checklist. It would be unusual for any one program for youth to demonstrate each and every one of the ten dimensions. Our hope is that the framework will support arts education practitioners in describing their work to others; that they will see some aspects of their work reflected in the ten dimensions; and that it will inspire them to reflect on and deepen their teaching practice in support of powerful arts education.